28/11/25

Touch and Travel: The Tactile Geographies of ‘the Blind Traveller’ James Holman

James Holman, a Royal Navy lieutenant who lost his sight at the age of twenty-five, was one of the most prolific travel writers of the early nineteenth century. Ross Cameron, Public Engagement Fellow, tells us about how Holman used touch to challenge the visuality of travel writing.

James Holman, the self-described ‘blind traveller’, met John Dundas Cochrane in Moscow in 1822. Holman was travelling east towards the Siberian city of Irkutsk on what he hoped would be a journey around the globe, while Cochrane was returning to Britain after his own travels in the Russian Empire. Cochrane did everything he could to dissuade Holman from travelling to Siberia and only reluctantly agreed to sell him his carriage and provide him with ‘a variety of particulars relating to [his] own proposed journey’. The spat between the two travellers did not end in Moscow. In his published Narrative of a Pedestrian Journey through Russia (1824), Cochrane asked how Holman could be ‘relied upon’ to write an accurate account of travel without ‘ocular evidence’?

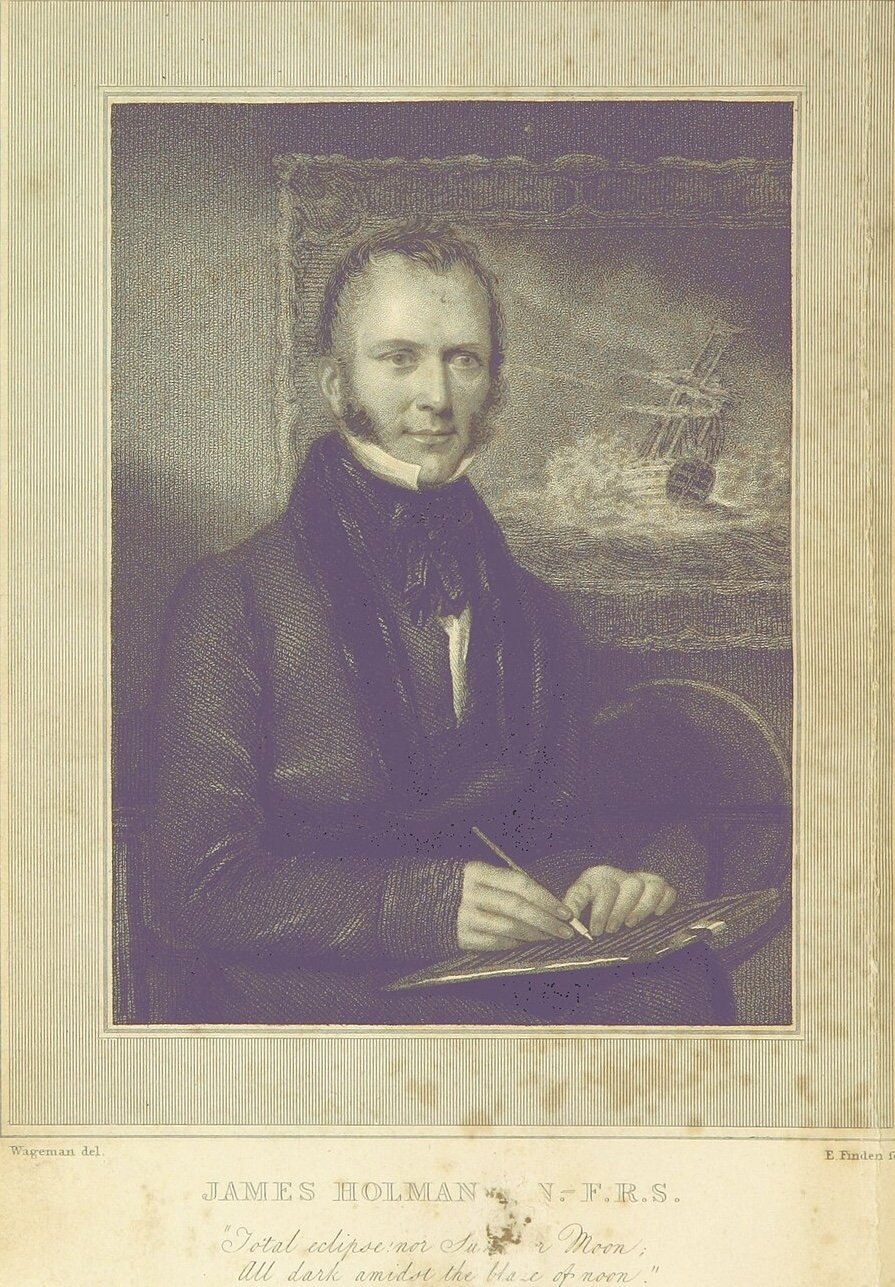

A portrait of James Holman in the frontispiece to A Voyage Round the World (1834). He is pictured with a ‘noctograph’ – a frame with metal wire stretched across to make horizontal lines – which he used to take notes while travelling.

The title page of Holman’s Travels Through Russia (originally published 1825), which includes his interactions with Cochrane.

Cochrane’s attack on Holman can partly be attributed to his bruised masculinity. ‘Who will then say that Siberia is a wild, inhospitable or impassable country when even the blind can traverse it?’, he asked. However, it also reflects the ocular-centric conventions of travel writing. As Charles Forsdick notes, travel writing demonstrates ‘the ways in which the visual has been progressively policed, framed, normalised, and also, particularly since the eighteenth century, increasingly privileged’. Whereas travellers once went abroad for discourse, to learn foreign languages and gain information in foreign courts, by the eighteenth century they increasingly went to see picturesque views or scenes. The changing sensory emphasis of travel was bound up with broader cultural changes that elevated sight in the hierarchy of senses by linking vision and empirical knowledge. The purpose of travel became to ‘sightsee’, a term that the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1824, the very year that Cochrane published his criticism of Holman’s method of travel.

Holman noted that he was ‘shut out’ from the dominant mode of travel that privileged the eye. Instead, he gathered information about the places he travelled through the touch of the hand. In Travels Through Russia (1825), he responded to Cochrane writing ‘my sense of touch is most delicate, and all that I require is to pass the hand lightly over the surface of a body, and then the result is both pleasing and satisfactory’. On his earlier tour through France and Italy, which he published as his first travel book, The Narrative of a Journey (1822), he visited the Vatican Museum and believed he was ‘as highly gratified as those who saw’. Holman wrote that through touch he gained ‘as clear, or at least as satisfactory, ideas of form and … the force of expression, as sight does to others’.

In the preface to the first volume of his epic A Voyage Round the World (1834), Holman argued that his method of haptic observation ‘impelled a more close and searching examination than the superficial view’, which gave his writing more veracity than the ‘first impressions conveyed through the eye’ that were recorded by sighted travellers. For Holman, touch was ‘less likely to deceive than the eye’, especially when it came to climbing mountains or ascending cathedral spires as ‘the dizzy height would make the brain turn, and the deficient sight topple down headlong’. Holman suggested his disability allowed him to go beyond the limits of sighted travellers. When climbing Mount Vesuvius, he recounted how his sighted companions wanted to turn back based on the visual evidence of spewing gases and molten lava, but that he continued the ascent until the rocks he grasped with his hands became uncomfortably hot and his walking stick was ‘charred’.

Despite adopting the masculine persona of a Romantic traveller, Holman’s sensory impairment was frequently imagined in feminised or infantilised terms by those he met on his travels. This perception of sexlessness, however, allowed him to keep the company of women he met on his travels and test the bounds of nineteenth-century propriety through touch. ‘If I find her conversation sensible and refined’, he wrote, ‘an opportunity is afforded me of feeling the hand, and touching, ever so lightly, the features of the face … their softness, delicacy, contour’.

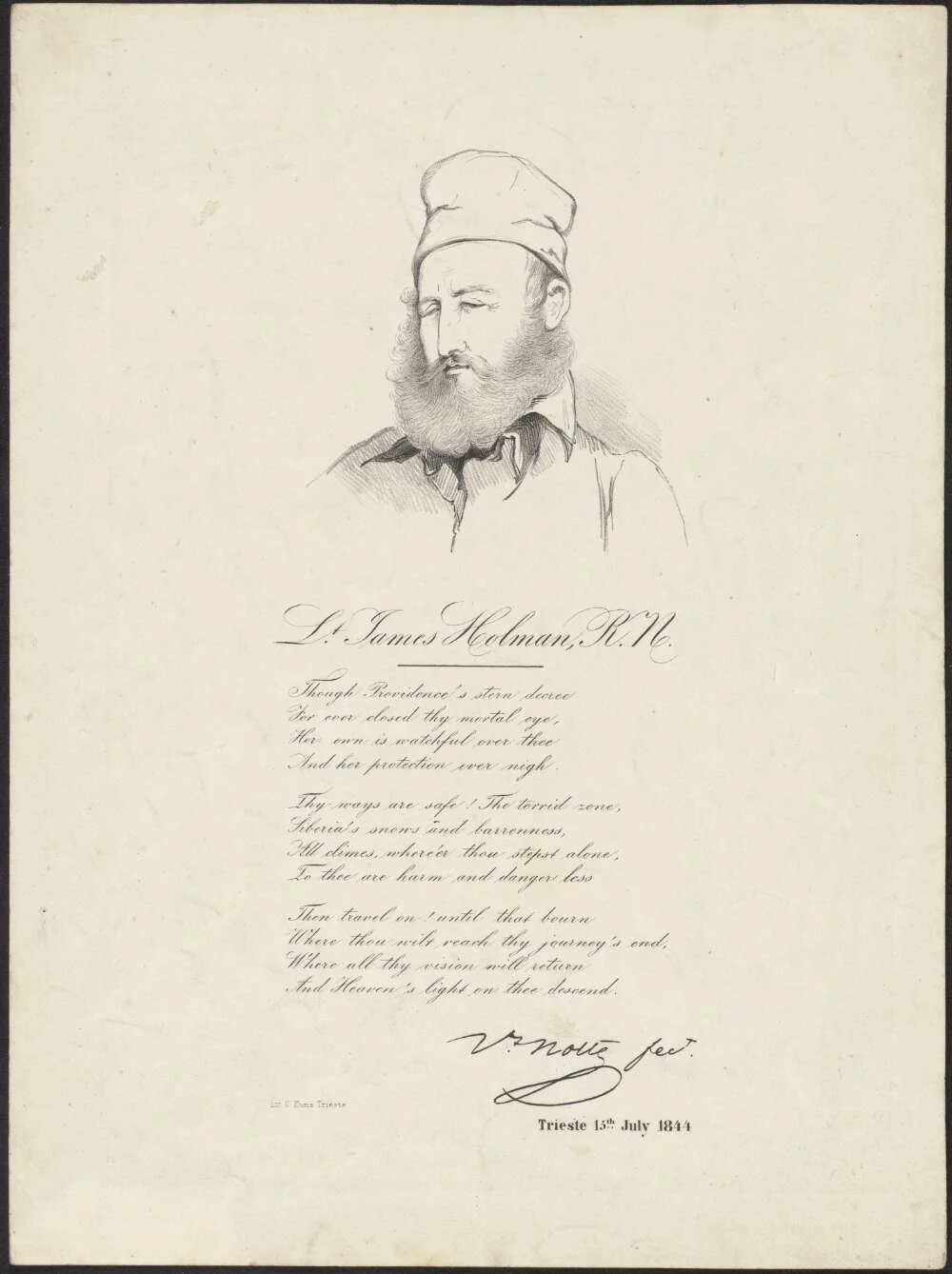

A lithograph of James Holman produced in Trieste, 1844, during his travels in southeastern Europe, held by the National Library of Australia. The narrative of Holman’s travels in the ‘Near East’ was never published.

A portrait of James Holman, with his walking stick, painted by the expatriate artist George Chinnery in Macau, 1830, held by The Royal Society, London.

Sarah Jackson, one of the plenary speakers at our upcoming The Hand: Emotions, Embodiment, Identity conference at the London College of Fashion, writes that ‘accounts of the tactile remain largely overlooked by both authors and critics of travel writing’. Critical focus has been on how the visual sense enables travellers to take possession of objects and environments at a distance, whether through ‘imperial eyes’ or ‘the tourist gaze’. Holman’s narratives, however, demonstrate the potential of travelogues to become spaces in which tactile geographies emerge and raise broader questions about how tactile engagement with, and representation of, space changes how we read travel narratives.

Nevertheless, Holman’s tactile geographies have limitations. He insistently touched everything, sometimes claiming that he ‘could with difficulty withdraw [his] hand’, but he rarely described the sensation of touch. There are passing descriptions of touch based sensations – the unpleasant texture of a fish he examined from the Volga or the coldness to touch of the statues in the Vatican – but these do not form a comprehensive tactile geography. When rendered into text, Holman’s haptic impressions evoke primarily visual encounters and landscapes. In one of the few critical studies of Holman by Eitan Bar Yosef, the visual language he deploys is attributed to his desire to be considered an authoritative traveller, rather than a curiosity, and the scientific conventions of travel writing before the genre’s shift towards impressionism in the later nineteenth century. While there is certainly validity to these claims, it overlooks Holman’s admission of his struggles in representing elusive tactile sensations, such as air pressure in humid climates, the brush of foliage in the tropics, or the wind atop a mountain, through language. Although touching his way around the world, Holman admitted, ‘I could have wept, not that I did not see, but that I could not pourtray [sic] all that I felt’.

Further reading

Charles Forsdick, ‘Travel Writing, Disability, Blindness: Venturing Beyond Visual Geographies’, in Julia Kuehn and Paul Smethurst (eds.), New Directions in Travel Writing Studies (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Eitan Bar Yosef, ‘The “Deaf Traveller”, the “Blind Traveller”, and Constructions of Disability in Nineteenth-Century Travel Writing’, Victorian Review, 35:2 (2009).

James Holman, A Voyage Round the World, 4 vol. (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1834)

James Holman, The Narrative of a Journey (London: G.B. Whitaker 1822).

James Holman, Travels Through Russia, 2 vol. (London: G.B. Whitaker, 1825).

John Dundas Cochrane, Narrative of a Pedestrian Journey Through Russia (London: John Murray, 1824).

John Urry, The Tourist Gaze (London: Sage, 1999).

Judith Adler, ‘Origins of Sightseeing’, Annals of Tourism Research, 16:1 (1989).

Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992).